Playoff success, who are the Jets, and what do they need to win

We look at the Winnipeg Jets microstatistics, and answer other analytical questions surrounding the team

Welcome to The Five Hohl

The best deep-dive hockey analytics blog focusing on the Winnipeg Jets. Also the worst. We’re 1/1—winner by default. Yay!

Today's article is a hefty one as we gear up for the trade deadline and prepare for the playoffs. We’ll take a critical look at the Jets’ strengths and weaknesses and how they compare to past Stanley Cup winners.

Originally, this was going to be one article, but it got reaaaaaally long. So, this is part one of what could be a two- or three-part series. The next installment(s) will cover specific trade targets.

In the meantime, I’ll also be dropping a short prospect update, plus a microstats breakdown for paid subscribers, either later today or early tomorrow. A bit of a disjointed week, but lots to cover.

WHO ARE THE JETS

The best way to determine what the Jets need is to first examine what they already are. We’ll start with their strengths and weaknesses as a team before breaking down the individual components.

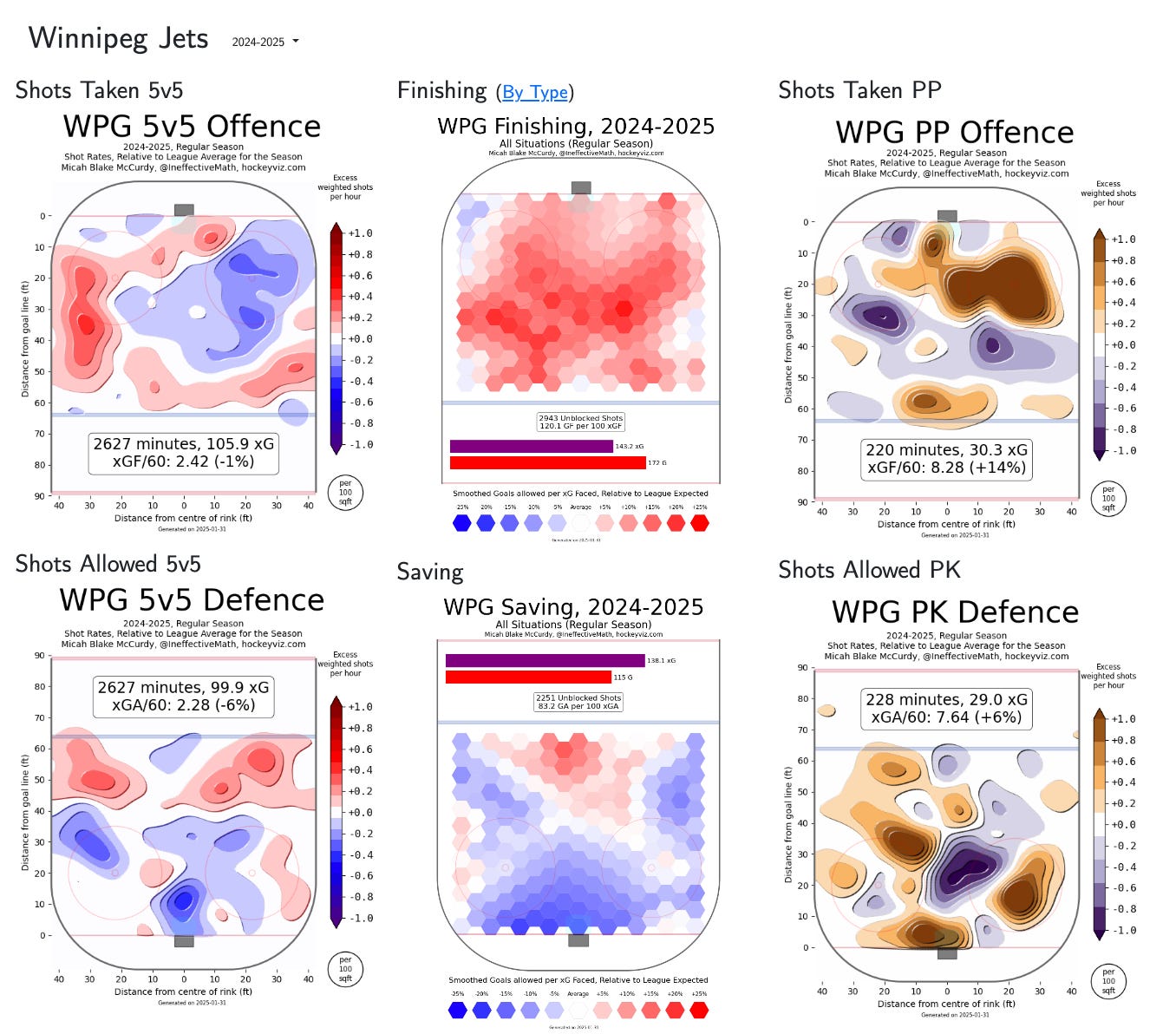

If you’ve followed my regular Monday reviews, you’ll recognize these visuals:

These charts display the Winnipeg Jets' performance in the six primary factors that contribute to outscoring opponents—ultimately leading to wins.

The top three categories focus on offense, while the bottom three cover defense.

The corners measure shot quantity and quality combined, while the middle sections evaluate conversion relative to those factors.

The left side represents 5v5 play, and the right side covers special teams.

Red/orange(brown) indicates performance above league average (good for offense, bad for defense), while blue/purple signals below-average performance (bad for offense, good for defense).

What the Data Shows

5v5 Offense: The Jets do not generate many chances at 5v5, making it a relative team weakness. While their numbers might look average, remember that they are competing against a league-wide sample—including teams that won’t even make the playoffs. The goal is better than average.

Power Play: This is one of the Jets’ biggest offensive strengths, also contributing heavily to their high-end finishing this season.

5v5 Defense: The Jets excel at preventing chances in even-strength play.

Penalty Kill: The defensive special teams unit has struggled, sitting well below league average—though it was even worse earlier in the season.

Goaltending: Historically one of the Jets’ greatest strengths, but this season’s overall performance has been dragged (slightly) down by Eric Comrie’s struggles. While Connor Hellebuyck has improved from last year, team-wide goaltending results have actually declined.

Comparing to Stanley Cup Winners

To better evaluate the Jets, let’s compare their six key performance areas to past Stanley Cup-winning teams and last year’s Jets squad.

Winning a championship isn’t just about being the best team—any team can win. However, being stronger in key areas increases the probability of success. Theoretically, given how often teams tend to beat other teams, we estimate the best team to win the Stanley Cup about 22% of the time. That’s about 3.5x better odds than random chance.

Among the six factors:

Goaltending and 5v5 offense are the strongest predictors of playoff success.

Penalty killing has the weakest correlation with championships.

Overall, offense has been more crucial than defense—especially after accounting for goaltending.

For offense, 5v5 chance generation is the best indicator of success, while finishing ability is less important.

For defense, goaltending is the strongest signal, while penalty killing is the weakest.

What This Means for the Jets

Defensively, the Jets are as good—or even better—than the average Cup-winning team. However, their offensive strength is concentrated in areas that historically matter least for playoff success. They are lacking in 5v5 chance generation, which matters most.

There is no single formula for winning a Stanley Cup, and the Jets are certainly good enough to compete. But with the trade deadline approaching, the goal should be to increase those probabilities as much as possible.

PLAYOFFS AND INTANGIBLES

Here’s a quote of one of my old works, that includes a quote from one of my even older pieces:

“Intangibles” in hockey are not actually pure intangibles. An intangible is something that cannot be perceived by the senses, like copyrights, patents, and intellectual property. Latent variables are things that impact a model (like outscoring your opponent) but you cannot measure directly, like leadership, confidence, morale, and happiness.

I have written on this before:

The reason why we care about “hockey intangibles” is because they are suppose to impact the results. If they do not, there is no reason to fuss over them.

You want physicality because it can wear down the opponent and may cause them to second guess entering a puck battle. You hit because you want to separate the player from the puck and cause them to lose possession. You play gritty because you want to win possession board battles and gain advantageous positioning over your opponents. You want leadership so players are in-tune to the coaches and their systems. You block a puck because you want to reduce the chance of a shot becoming a goal against.

Hockey “intangibles” are attempts to improve the team in the shots and goals columns. Their effective impact is real and theoretically measurable, even though it is (at least currently) impossible to track them directly.

I also spoke on the subject previously at Hockey-Graphs:

In the end, we cannot directly measure their impact, but they matter because we assume they have an effect on shots and goals.

This means that these values should matter. However, they should not matter more than the on-ice product. There is a greater unknown factor, and therefore risk, with latent variables. Without the ability to measure their impact, it becomes difficult in testing how much they matter and whether you are evaluating players with them appropriately.

The Jets’ current performance already accounts for the intangibles they possess. The team generates and prevents chances because of how all their traits—size, physicality, strength, speed, leadership, grit, hockey IQ, positioning, etc.—interact with one another.

Rather than targeting specific qualitative factors, the Jets should focus on on-ice needs and measurable player performance.

PLAYOFFS ARE DIFFERENT

There’s an argument that the playoffs differ from the regular season. I agree to an extent, but I’m skeptical about how much that difference should influence player acquisitions.

The key question: Can we accurately predict "playoff intangibles," and can we effectively trade-off on-ice performance for them?

While analytics don’t predict playoff performance with 100% certainty, we do know that measurable trends and relationships exist—ones that can be exploited with a degree of success.

Getting back to the playoffs…

The playoffs bring higher intensity and pressure. Human responses to this vary, but NHL players are already part of an elite talent pool. Through years of selection and development, these athletes are better equipped than most to handle playoff hockey pressure.

That’s not to say NHLers aren’t affected by playoff pressures—but rather that these pressures likely impact most players in similar ways and amount. Some playoff effects may be uniform, affecting all players equally. And being able to overcome them as a skill may correlate highly with existing skills, meaning regular-season performance is still a strong predictor.

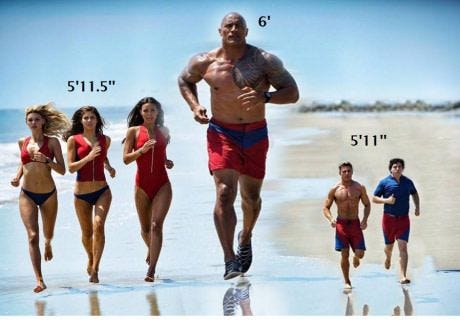

The same logic applies to physicality.

Yes, playoff hockey is more physically demanding, with less space and tighter checking. But how much of that is simply due to the increased competition (i.e., removing the bottom half of the league)? Performance metrics already adjust for competition levels, so this aspect of the playoffs is at least partially accounted for.

At the end of the day, it’s still hockey—and the players who succeed in the regular season against top competition should have a reasonable expectation of performing well in the playoffs.

It’s not that playoff differences don’t exist—it’s that we don’t know their extent and how to determine them reliably. This makes it risky to lean too heavily on intangibles when we have clearer, measurable performance indicators.

Because of this, I typically suggest using “intangibles” as tie-breakers between similarly performing players or as deal-breakers when red flags exist.

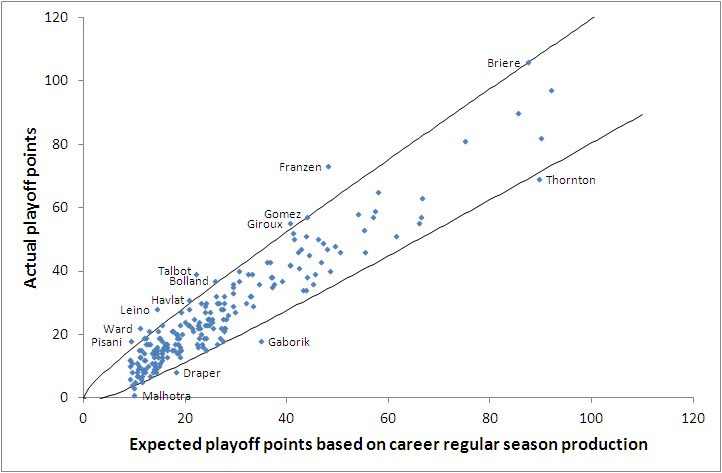

Looking at empirical evidence, Eric Tulsky (now the Carolina Hurricanes GM) once analyzed regular-season versus post-season performance in an article that, unfortunately, is no longer available online (I even looked the Wayback Machine). In his research, he adjusted for differences in shot rates, goal rates, and other factors between the regular season and playoffs. His findings showed that player performance in the playoffs was no different than what we would expect based on regular-season performance—once you account for smaller sample sizes and the natural fluctuations seen in hot and cold streaks.

Luckily, I still have one of the graphs saved on my computer:

This isn’t to say that some players don’t perform better or worse in the playoffs. Instead, it means that variability in playoff performance is expected and falls within the normal range of statistical noise.

For example, there’s no way to say for certain that Nikolaj Ehlers has scored less in the playoffs because he struggles in that environment. It could just as easily be a result of normal performance fluctuations. Based on Tulsky’s findings, his next playoff run is just as likely—if not more—to reflect his usual regular-season production.

Dom Luszczyszyn of The Athletic conducted similar research when building a playoff performance prediction model. His results suggested that 90% of a player's playoff outlook should be based on regular-season data, with only 10% weighted on past playoff performance. This further reinforces the idea that regular-season success is the strongest indicator of postseason effectiveness.

PLAYOFFS AND (DEFENSEMEN) SIZE

For a long time, many have believed that size provides an extra advantage in the playoffs relative to the regular season. Essentially, the idea is that adjusting regular-season performance for size would improve playoff predictions. The argument is the tight, physical, and grinding nature of the playoffs gives size an extra advantage.

Two major research articles have supported this hypothesis, but I have issues with both. This time, I’ll focus on the one about defensemen.

However, one key flaw in both studies is that this supposed effect only appears when looking at specific recent samples. If you expand the dataset further the effect disappears.

That would be fine if the argument were that the game has changed, but decision-makers have long claimed this effect has always existed, due to an environment that has never been argued to change.

Issues with the Study Supporting Bigger Defensemen

The study in question had several problems. While it was useful for hypothesis exploration, it was not strong enough to support the hypothesis.

The author calculated the average height and weight of forwards and defensemen for each team, then categorized teams into "larger" or "smaller" groups based on a 5-pound or 0.5-inch difference. This created eight different comparisons (2 positions × 2 measurements × 2 size groups), and the study concluded that bigger defensemen provided a postseason advantage.

What the study actually found was:

Larger teams had +1.5% to +4.7% better regular-season points percentage, depending on measurement and position.

Larger teams had -3.3% to +11.4% better playoff win percentage, depending on measurement and position.

Now, let’s break down the problems…

Points Percentage vs. Win Percentage

The study compared points percentage in the regular season but used win percentage in the playoffs.

This is an issue because points percentage is inflated by the "loser point", which awards teams half a win for reaching overtime. Since about 20% of losses come with this bonus point, it artificially narrows the gap between stronger and weaker teams in the regular season.

This skewed the results in the study.

Cherry-Picking Significant Results

If we look strictly at win percentage, the study’s results change:

Taller defensive teams: +6.5% playoff win percentage

Heavier defensive teams: +7.7% playoff win percentage

Taller forward groups: -4.7% playoff win percentage

Heavier forward groups: -1.0% playoff win percentage

The study highlighted the taller defenders’ advantage while downplaying the negative impact for taller forwards. But if the data really suggests teams should target bigger defensemen, then it also suggests they should actively avoid bigger forwards.

It also raises a bigger question: If bigger defensemen have an advantage, why would bigger forwards—who battle them—be at a nearly equal disadvantage?

Marginal Size Differences

The study binned teams in games into two groups based on whether one team was at least half an inch taller or five pounds heavier.

But those differences are tiny.

For example, I’m 6’2" and around 190 lbs, but I’ve fluctuated between 188 lbs dehydrated in the morning and 195 lbs at night just from eating, drinking, and daily spinal compression.

(I actually tested this for accurate numbers for this article—you’re welcome.)

That’s a weak threshold for categorizing teams into "big" and "small." Especially given how inaccurate the size measurements of NHL data tend to be.

Ice Time Matters

This is a smaller issue (pun intended), but size alone isn’t the real factor—it’s who is playing the key minutes.

A team might be "bigger" simply because they have a 6’7” depth defenseman who barely plays, and when they play are hid from the opponents’ best and high-leverage minutes. That’s not the same as having prime Victor Hedman logging 25+ minutes a night.

To accurately measure impact, you need to adjust for ice time rather than just looking at team averages.

Binning Continuous Data

Binning (categorizing continuous variables into groups) can be useful for visualization, but it distorts real differences.

When you bin height and weight, you treat:

A one-inch difference the same as a two-inch difference.

A one-goal win the same as a four-goal win.

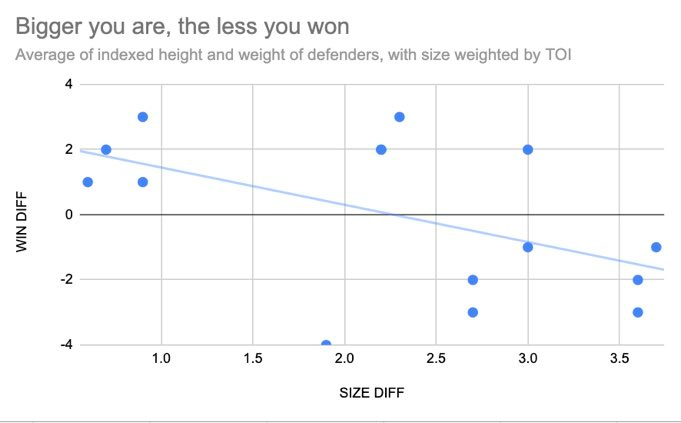

Last year, I recreated the study but combined height and weight into an index (adjusted for ice time) for the playoffs. The results?

The smaller defensive teams actually won slightly more games.

While the effect was in the opposite direction, it was small.

However, here’s the kicker, when you look at the scale of size differences things change. Most of the series wins for the larger team were when the differences in size were small. In the series where the difference was large, the smaller teams won more often and much more decisively.

Scale matters. Without scale, this small sample would make it seem like being a smaller defensive team was a small advantage, but in actuality it was quite large.

Too small of a sample to say that’s actually the effect, but it shows the issues of how binning can muddy results from reality.

Position vs Position Comparison

Another flaw is how the study compared defensive size between teams.

It assumed that bigger defensemen gave a direct advantage over the opposing defensemen. But that’s not how matchups actually work.

Defensemen don’t battle each other in front of the net. They battle forwards.

So, does the 14th-largest defense in the league really have an advantage over the 16th-largest in the playoffs—regardless of how big the opposing forwards are?

Size is a Skill

Size is just another tool—like skating, passing, shooting, hockey IQ, or work ethic.

It’s not inherently good or bad; it’s an input that contributes to a player’s overall effectiveness.

Analytics people don’t ignore size. The real goal is to find the best players—if they’re effective because of size, great. But size alone isn’t enough.

Final Thoughts

To be clear, I’m not arguing that size is a bad attribute. My beliefs are:

Size is already accounted for in performance models. Players are as good (or bad) as they are because of or despite their size. Giving it extra weight could lead to double counting its value relative to other factors that are just as important.

No strong evidence exists that size provides an extra playoff advantage. Looking at player performance in regular-season vs. playoffs (adjusted for usage), we don’t see a real effect in either direction.

Some reverse causation may be at play. Already strong teams that lack size may specifically target bigger players at the trade deadline—especially in depth roles. This would inflate team averages without necessarily improving their chances of winning.

The Jets do not need to target defensive size.

STYLE AS A FIT FOR SYSTEMS AND ROLE

Last year, the Winnipeg Jets acquired three highly effective analytical players in Tyler Toffoli, Sean Monahan, and Colin Miller. However, despite their individual contributions, the overall team performance didn’t quite reflect the sum of their parts.

I think there are two key reasons for this:

First, there’s the issue of style and skillset alignment with systems. Under Rick Bowness, the Jets' system was most effective when they used their speed to aggressively pressure their opponents. While Monahan and Toffoli were better forwards than the ones they replaced, their slower footspeed hurt the Jets' transition game and ability to implement that aggressive forecheck, diminishing their overall impact relative to their individual skill.

Second, the players didn’t always play to their strengths. Colin Miller, for instance, was healthy scratched in favor of Logan Stanley, who was asked to play on his off-hand side—something that made little sense, both in terms of skill set and team needs.

JETS ROSTER FOR NEEDS

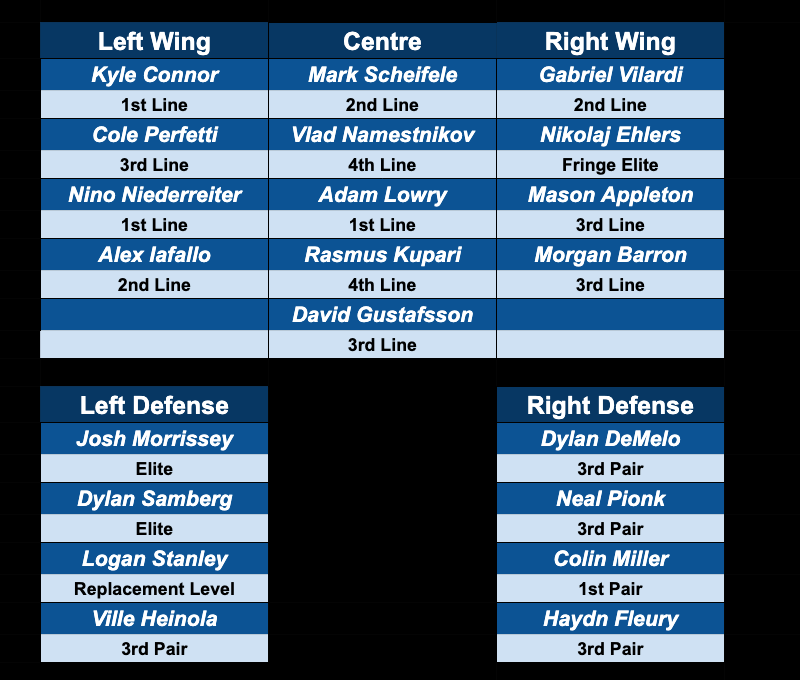

Using HockeyViz’s sG model, this is essentially how the Jets’ depth chart looks in terms of performance once adjusted for deployment:

FORWARDS

The Jets' forward group is solid but not exceptional. Depth is one of their strongest assets, and the distribution of talent has worked out well overall.

The Jets have at least one top-line-performing forward on each of their top-three lines, and their fourth line features two middle-six-caliber wingers. This setup allows the Jets to attack in waves, making it hard for opponents to sustain pressure. If one line goes through a rough patch, the others are more than capable of picking up the slack.

Diversification is the only free lunch:

These are strong numbers, as no line is performing below average. However, it's important to keep in mind that this data reflects regular season performance when the bottom half of the league is still in play. For example, the eighth-ranked team in each of Corsi, xGoals, and goals has a 52% Corsi, 52% xGoals, and 53% goals percentage. The Edmonton Oilers (the eighth-ranked team in goals %) are at 55% in both Corsi and xGoals, which surpasses the Jets’ top-three lines in both metrics.

It should also be noted that the Jets' goal performance exceeds their Corsi and xGoals largely due to strong on-ice save percentages, notably from Connor Hellebuyck. As a group, the Jets' four forward lines have scored almost exactly as many goals as expected based on shot quality and quantity, but they’ve allowed about 19 fewer goals than expected.

While the Jets have been solid at 5v5 across the board, there is still room for improvement to elevate them into true contender status.

The Jets' most obvious gap, which everyone knows about, is the need for a better center for Nikolaj Ehlers. This could be addressed in a couple of ways:

Ehlers could skate with Adam Lowry, and Cole Perfetti could be upgraded from Vlad Namestnikov.

Alternatively, Perfetti and Ehlers could remain together, with a new center added between them.

Either option could work, but ideally, the Jets need a center with enough speed and intelligence to complement Ehlers’ game while also helping improve the Jets’ three weakest areas: 5v5 offense, penalty kill, and the second unit power play.

5v5 offense is particularly important for playoff success and is the Jets' second weakest area compared to other teams. While penalty killing isn’t as crucial for playoff performance, it’s still an area where improvement is needed.

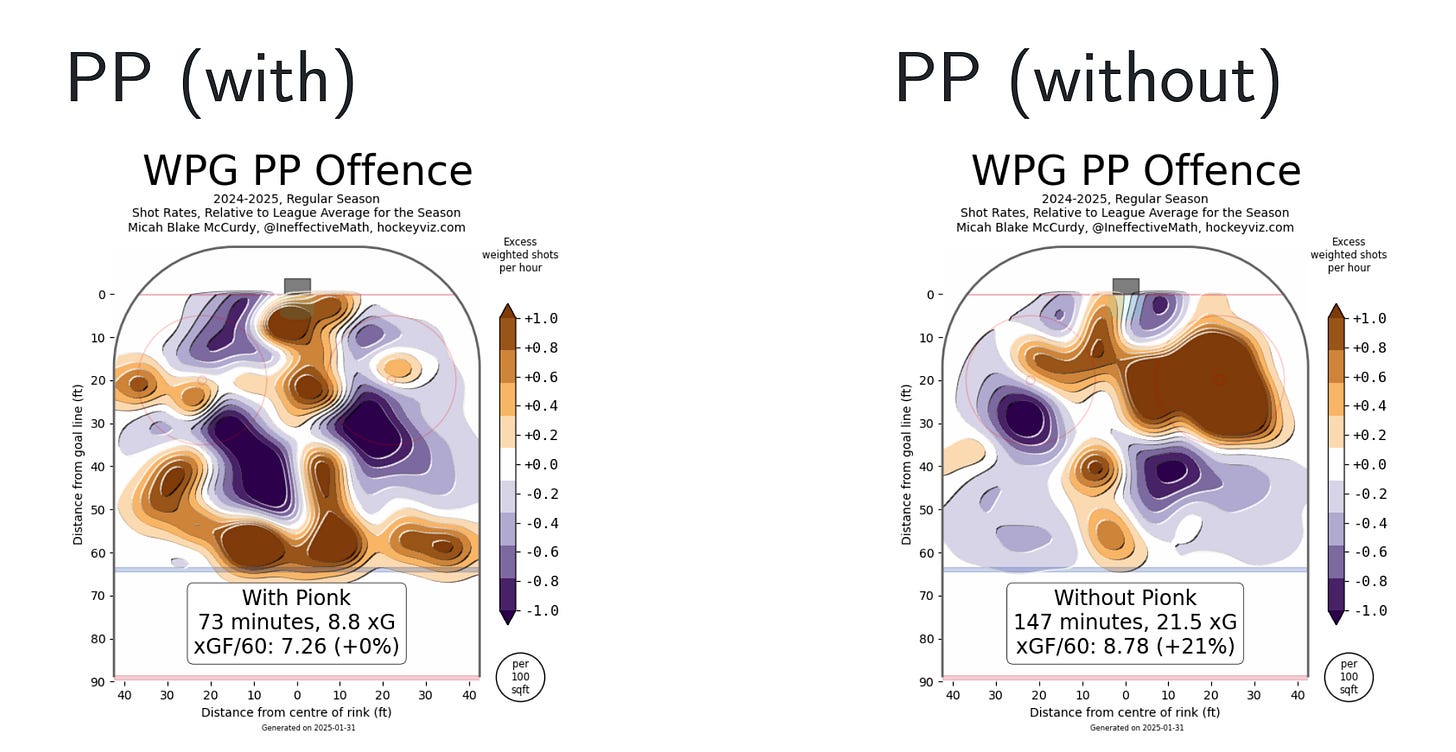

The second unit power play may come as a surprise. While the second unit has scored at a high rate, their actual chance generation has not been as impressive as the top unit’s. Here’s a comparison of the shot charts, with the second unit on the left and the top unit on the right:

Adding a top-six center who can contribute to the penalty kill and strengthen the second power play unit would be a game-changer. This would also take some pressure off the Jets' top line at evens, which —while better than last year’s subpar performance— still falls short of being among the top quartile of first lines (with ~54-55% Corsi and goal percentages marking the threshold for first-line performance).

A top-six winger would be a good addition in case of injury but isn't as crucial for the Jets’ needs and might not bring as much of an improvement.

I’m confident we’ll see a step forward from Perfetti if we can secure an upgrade for his center. Perfetti is a cerebral player, and much of his impact depends on the quality of teammates he plays with. I also don’t want to see him healthy scratched in the playoffs again.

DEFENSE

Figuring out what the Jets should realistically do with their defense is actually quite challenging.

On the left side, you have two players who are exactly what you want: Josh Morrissey and Dylan Samberg. You couldn't ask for much more from them.

However, their partners on the right side leave a lot to be desired. Neal Pionk has been solid when paired with Samberg, pulling himself out of replacement-level play, but he’s been an utter train wreck with anyone else. Meanwhile, Dylan DeMelo has been a shadow of his usual self, possibly due to a chronic or nagging injury.

You likely need to upgrade one of these right-side defensemen in the top four, but the problem is that doing so might involve scratching someone who could be an upgrade, like Colin Miller.

The not-so-easy solution would be to find a trade partner for Pionk or DeMelo, but as always, that’s easier said than done. After all, this isn't NHL on Playstation.

Then there’s the bottom pair, left-shot defender.

The main issue here is Logan Stanley, and frankly, I’m tired of beating a dead horse.

Third-pairing defenders typically have a diminished impact due to low ice time and low-leverage deployment, but unfortunately for the Jets, that’s offset by poor play on the penalty kill and one of the worst career penalty differentials in the league.

Ville Heinola offers some potential, but unless the Jets trade Pionk, it's a hard sell with Heinola not being trusted on the penalty kill or for a spot available on the power play. Haydn Fleury has been comparable to Heinola at 5v5, and while he's been trusted to kill penalties, he probably shouldn't be.

So, the Jets could certainly use a third-pairing left-shot defender upgrade.

Ideally, this player would be trusted to kill penalties (unlike Heinola) and actually be effective in that role (unlike Stanley and Fleury). You also don’t want them to be a 5v5 anchor (unlike Stanley).

A top-pairing right-shot defenseman would be a nice addition obviously, but that would be hard to achieve without significant changes to the Jets’ defensive roster. Issue is how do you add them and not scratch Miller to take full advantage of the upgrade.

It’s a small sample, but Samberg-Miller has about the same Corsi% as Samberg-Pionk. I’m sure DeMelo —who still has a very strong defensive impact— would be a great partner for Heinola on the third pair in a more sheltered role.

But, the Jets like Pionk. He’s passed DeMelo for second on team’s average ice time since around the 20 game mark.